Teaching and Learning Resources

Graduate Student Supervision

The following notes were captured from a McMaster workshop on Supervising Graduate Students on February 20, 2006. Experienced faculty at this workshop were:

Harold Haugen – Department of Engineering Physics

Allison Sills – Department of Physics and Astronomy

Michael Veall – Department of Economics Chair

Elizabeth Weretilnyk – Chair of Graduate Studies, Department of Biology

Lorraine York - Department of English and Cultural Studies

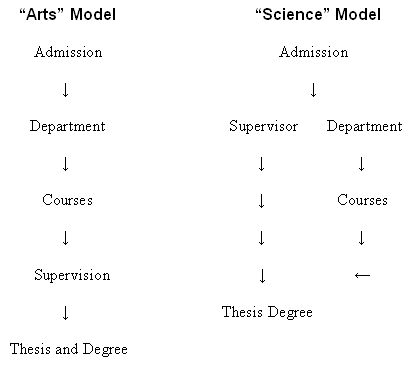

The process for admitting students to a masters or PhD program and accepting a student as a supervisor varies across faculties and generally follows one of two models. Departments vary in the specifics of their procedure but the process is roughly as you see here and as described below. The questions in this document come from across disciplines and address questions from both the Arts and from the Sciences.

In the Arts, students are generally admitted to the department and begin to complete their courses. They are accepted by a supervisor, complete their program requirements and their research then proceed to write the thesis and earn their degree. The student’s research is in an area related to that of their supervisor. Students in the arts interact regularly with their supervisor with the frequency depending upon the stage of the research. They may meet several times in a semester. Students usually pursue their own research funding. A student’s research does not require interaction with other students in the program.

In the Sciences, students are generally accepted first by a supervisor then they must be accepted by the department. They begin to work directly on their area of research at the same time as they begin their coursework. They complete their program requirements, complete their research, proceed to write the thesis and earn their degree. The faculty supervisor usually pursues external funding for their own research program which funds costly research equipment, materials, and graduate students. The student’s research is usually directly or very closely related to the supervisor’s research program. Students in the sciences often work closely in a laboratory, interacting almost daily with the supervisor and other graduate students in the program. This interaction is often necessary to complete the research in order to then proceed to write the thesis and earn the degree.

Making Decisions about Accepting Grad Students

What is the role of the graduate student supervisor?

- Your actions model “how to be” in the profession, this is particularly true for female faculty members where finding balance is more challenging. Students see what you value in how you divide your time, and how you juggle your work and family responsibilities.

What should I do to prepare for graduate student supervision?

- Become familiar with the structure of graduate programs in your department, i.e. steps, stages, and deadlines. Find out if your department has a graduate brochure explaining who can serve on graduate committees and what structure it should take. Find out as much as you can about program requirements, flexibility and constraints. Be mindful of time and completion and try to get a sense of the norms within your department.

What logistical issues do I need to consider before accepting graduate students?

- If you are approaching a year of research leave, how will you handle supervision of your graduate students? i.e. What stage will your graduate students be when you take your leave? You can’t leave your graduate students high and dry without support. You need to plan for regular, appropriate supervision and open channels of communication.

When should I begin to accept graduate students and how many?

- This differs widely across campus. Confer with the department chair, graduate student advisor, or chair of graduate studies in your department to get a sense of what is considered to be an appropriate supervisor load. In some cases, there may be limits set by the department.

- Check departmental guidelines and talk to colleagues about the time required. Do a rough calculation of the hours required to properly supervise the number of students you are considering. This will be your ultimate reality check.

- Younger faculty feel pressured to graduate lots of students for tenure and promotion, consider how many grant proposals will be required to support the students. If you are planning to become a parent consider how much time you will have for graduate students given paternity or maternity leave.

Can I refuse a student? Is personality enough of a reason not to accept a student?

- You are under no obligation to accept a graduate student. It is bad idea to accept a graduate student if you expect you will have difficulty working together.

What questions should I ask prospective graduate students?

General

- In what way do you hope I will contribute as your supervisor?

- What input do you hope my research interests will connect with yours?

- What are your expectations of graduate work?

Work Habits and Interests

- What sort of meeting schedule will work for you? How often do you think we should meet?

- What time of day do you prefer to work? What time of day do you prefer to meet?

- What do you like to do in your spare time? This may be helpful if you are looking for students

- with particular interests and aptitudes. One professor whose research involves a lot of

- computer work looks for students who like to play with computers in their spare time.

Supervision and Future Goals

- Are you interested in mentorship directed toward a career in academia or another career? Approach this question with care. Many students don’t know what they want to do and will tell you they want to be professors and want to do the same research that you do. Students may believe you will only accept those who say they are aiming for a career as an academic. If you will accept those who have different career aspirations, let them know. You may find they will be more frank about their goals and you can plan appropriately.

Research Questions

- How do you perceive my research program? (Are they really interested?)

- Have you done any research? Have you done an undergraduate thesis project?

- Tell me about your research? Tell me about your research interests?

- Do you have any questions about how I do my work or how I run my lab?

- Ask them how they pursue their research, for example, what questions might they like to ask?

Those who can answer these questions tend to be the better students.

What should I consider before accepting graduate students?

Questions from Science and Engineering:

1. How much space, access to equipment, ancillary space to set up projects, and space near the lab

will the student require?

2. How much will it cost to fund a Masters student? A PhD student?

3. How much time and money will it cost to bring students up to speed in your research area using

particular research methods? Training is very expensive in some areas of research.

4. How much time will student supervision take? How often will you need to meet? Keep track of

personal time. It takes more time than you might expect. Ask some of your newer colleagues

how much time it takes.

5. What types of project will you choose for students? It will take a while to set up a working

lab? Take this into account in your planning.

6. If you have a large lab with multiple students, senior students can play a role as mini mentors,

but they don’t have a professor’s experience, and have their own work to do. Your role is to

provide guidance and big picture direction over groups of students. Safety and training is

important and must be addressed explicitly.

7. Are you comfortable reviewing and criticizing student work?

How do I decide if I should accept a particular graduate student?

- Your department will help you decide if the student meets the criteria for admission.

- Marks are not a good indicator of the “chemistry” you will have with your graduate students. You can’t look at files and necessarily pick a good student.

- Take any opportunity you can to pre-interview students and meet face to face. If this is not possible, there are alternatives. For example, you may be able to meet at a disciplinary conference you are planning to attend. At the very least, get contact information and plan to telephone the student and speak to them directly about your discipline. If you are considering an international student, this will give you an opportunity to informally determine their level of skill in speaking English. Some faculty members make this an unscheduled call to ensure they are speaking to the actual student they are considering.

- Develop a gut feeling about the student by talking with them. Ask yourself whether you feel you could work with this person. What is your initial impression?

- International students with excellent transcripts are hard to compare. Some faculty members use institution rankings of international universities to provide some sense of the quality of student preparation.

- It is worth the effort to recruit the best students you can. That doesn't always mean selecting those with the best grades. Evidence that students can work independently and as creative researchers is more important.

- Send senior graduate students out to have lunch with potential new graduate students so they can talk frankly about the experience of working with you. Later, you can ask your students for their impression of the prospective student.

How do I handle issues of intellectual property? (e.g., sharing patents with graduate students)

McMaster policy addresses issues of patentable material. The office of Research Contracts and Intellectual Property (ORCIP) can help clarify these issues.

- Be very careful from the beginning regarding what can be disclosed in meetings. Graduate students will need guidance regarding restrictions that apply to public dissemination of research work. However, research disclosure agreements cannot interfere with a student’s ability to proceed with their program.

How much time should a student spend on their own versus their professor’s projects?

- This varies—depending on the graduate student and project.

- Some students like to get immersed immediately in clearly defined projects, so give them one. Some students prefer to do their own thing. One student had a specific project in mind which turned out to already have been done elsewhere requiring guidance and a rethinking.

- If there is someone else on campus with expertise in the area of the student’s interest, they may be willing to help coach them.

How do I create student cohesion in a research office?

- Try to get students out of the “undergraduate” frame of mind. Undergraduates are used to being available only during class hours, whereas graduate work is quite different. Change the expectations about how much time to spend in the lab and expectations for interaction and work hours.

- Provide opportunities for informal gatherings.

What is important to consider in writing letters of reference?

- The objective is to “unite civility and truth in a few short sentences” (Austen). It is important to always be honest in a carefully coded way, though too much coding can fail to communicate. For example, if you have reservations about a student, you can say something about recent “improvement”, or their response to criticism. A good letter provides detail with specifics about the individual. Letters from foreign sources are not always helpful and can be hyperbolic.

Some useful strategies to consider,

- Ask the Chair for sample letters of reference.

- Ask the student to provide you with a little portfolio of assignments and their curriculum vitae so you can mention specifics; have a short conversation with them to obtain some specifics for the letter.

- If you know the referee, you could call them to follow-up on the letter,

- Ask the graduate student to write their own letters for you to modify.

- Letters of reference—it’s okay for committee members to show each other the letters they are preparing. Share to ensure you are saying what you think you’re saying.

Getting Students Off to a Good Start

How can I get students off to a good start in Science/Engineering?

Meeting and guidance

- Plan regular meetings and provide regular coaching.

- Give students the sense that you are available. Provide ongoing direction without micro-management.

- Provide some combination of full group meetings with groups of graduate students, individual and small group meetings, complimented by departmental meetings.

- The full group might meet every second week.

Resources

- Provide reasons for students to use all resources.

- Get students to stop thinking they must be completely self-sufficient and encourage them to work with others, to exchange ideas and to exchange strategies.

- Emphasize ownership—commitment, motivation and being proactive.

Get students to take responsibility for their work and progress

- I try not to set deadlines so they will take responsibility for doing so.

- I don’t get too highly structured so as not to stifle creativity.

- Expect and establish good work patterns. Ask them about the plans, milestones, and deadlines they are setting for themselves.

Encourage students to get out of undergraduate mode

- Consider placing students offices to be physically close to the lab—to get them out of “undergraduate” mode which requires they only show up for class.

Concerns

- Because of safety concerns, I want them to work during regular working hours. If equipment is potentially dangerous, it doesn’t matter if it is available in the middle of the night. Accidents can easily result from fatigue.

Get students discussing research results early in their program

- Encourage students to attend conferences early and to participate in poster sessions.

- Try to get them students to a high profile conference. Conferences can be really motivating.

- Send students to other labs to get experience not available in your lab. They usually come back full of ideas. Helping students develop a network of colleagues can increase the likelihood of this happening.

How can I get students off to a good start in Social Science?

The committee decides on a proposal which forms an implicit contract with the student.

Meetings

- Regular meetings or reports can really help students remain focused. This can take various forms including email. For example, one instructor had a part time student who would send a weekly report of her activities. This demonstration of productivity actually encouraged the faculty member to be more productive.

Writing the thesis

- The prospect of writing a thesis can be overwhelming. Consider presenting the requirement as a series of papers or some other series of things that add up to a thesis rather than as a single document.

Danger signs

- It is a bad sign if the student talks a lot about how much time they are putting into graduate work.

Importance of focus

- Students who run out of funding can lose all focus and fail to complete. Work to help them meet the requirements within the funded period.

Standards of performance

- Try to maintain a high (but reasonable) standard of performance for students. Don’t vary standards per student; it does a disservice to the field.

How can I get students off to a good start in Humanities?

Meetings

- Unlike a Masters degree, the first meeting for a PhD doesn’t settle everything. Consider a series of meetings.

- Hold initial meetings in neutral space such as a coffee shop rather than your office to decrease the hierarchy and encourage students to take more responsibility for their own work.

Ownership

- Encourage students to articulate their ideas in a setting they may find safer such as an informal discussion group (for a five-minute discussion) without the instructor present. Ask students to spend five minutes describing where they think their research is going.

Professionalization

- Graduate seminars can start to develop skills such as oral and written presentations.

How can I get students off to a good start in Science?

- Try to gauge student capabilities. For example, do they need to see data quickly? If so, get them working with data quickly.

Get students to take ownership

- Don’t launch them on a big, defined project. Connect them with someone else in the lab to work alongside

- Provide students a copy of your discovery grant so they can see the big picture. This provides the student with the nuts and bolts required to reach research objectives. Help students see their part in the larger project.

- Provide orientation to the lab, to other graduate students, and to peer support.

Provide incentives

- Offer to send students to meetings, not to give a presentation but to give a poster. This can provide an early opportunity to write and obtain feedback and delay the oral presentation.

Writing the thesis

- Get students to think in chunks, like a paper with a theme to it. For example, Chapter/Poster/Abstract is an easier way to think of this task.

How often should I meet with students? One-on-one? Whole group?

One professor in science uses a variety of meeting formats including:

- Half-hour meetings with the full group of students to discuss issues.

- Weekly group meetings—most students spend two minutes providing an update. Beware of those that don’t show up or are silent. They often have problems.

- Regular meetings with each student to catch “student” problems. The student who is missing meetings and seems to be avoiding you is often the one who most needs to meet. Sometimes the student is stuck and doesn’t realize it.

- Targeted meetings with a smaller group to address specific issues on a topic bringing in others as needed.

- 20-minute, individual presentations. Just bear in mind some students hate being put on the spot.

Is there a benefit to meetings with groups of students?

- Since time constraints make it hard to meet with each student, group meetings can be very helpful as problems can be brainstormed together. Group meetings pull people together with common concerns. They can also help with presentation skills, providing an less formal opportunity to stand up and speak. Some students don’t like this, but speaking is an important skill to develop. One disadvantage is these meetings can be hard to schedule.

How do I get students to think like a professional in my discipline?

- Get your students reading the literature and thinking about writing.

- Encourage students to engage in public speaking early with repeated opportunities for feedback. This can involve mini assignments such as reading abstracts of papers, presenting an analysis and discussing it with groups of other students.

How do I move students to the role of independent researcher?

- Encourage students to be proactive early and tell them you expect them to take initiative and see what happens. There are probably norms regarding when students in your discipline are expected to start presenting and writing. Let them know about these expectations.

- You will know students are starting to become more independent when they begin to ask disciplinary questions. They begin to take ownership of their project indicating they are ready to move forward. You will know they are on the right road when the student starts talking about what they will do next.

What skills should I be trying to help students develop?

Skills include:

- Writing a proposal

- Writing a literature review

- Reviewing papers

- Giving a presentation

- Writing grants

- Administration

- Supervising other graduate students

- Teaching

- Writing a review

Troubleshooting

What can I do when a graduate student isn’t working out? How much can you expect students to do?

- A supervisory meeting must take place at a very minimum of once per year. If there are problems, meetings should be set more frequently.

- A supervisory committee can be put together at any time and can provide suggestions and guidance. The group can judge what kind of progress would be considered reasonable. A statement from a group regarding expectations may carry more weight than a single supervisor.

- Set time lines and milestones to be reached. Clarify expectations and confirm these in writing to reduce any possibility of future confusion or ambiguity. This can be as simple as sending an email to confirm what was agreed at the meeting.

- Sometimes there are competing pressures on a student.

- Ask what the student has been doing, i.e., coursework, demands working as a teaching assistant other outside commitments, or family commitments.

- Ask if the student is encountering obstacles. Sometimes you can remove, address or reduce obstacles, e.g., faulty equipment, frequent interruptions etc.,

- Remember students need a life too. They may have a spouse, children or other family commitments. We often expect our students to behave as we did. They are not always as driven and may not be aiming for an academic career. Faculty members are not usually the “average” student or average grad student; you likely worked harder, longer, and were probably more productive, which ultimately resulted in success in landing the faculty position.

- Are there conflicting interests where a supervisor needs a publication for the next grant. Is this a fair pressure to put on the student?

What can I do about student writing problems?

- This very time consuming problem is not restricted to International students. Many students have focused on other disciplinary skills and not developed their ability to write clearly and concisely. The Centre for Student development (CSD) holds Academic Skills Workshops and a Writing Clinic with peer tutors to provide feedback on writing with a focus on skill development.

International Students

- One way to gauge the writing skill of a prospective student is to look at emails sent to the graduate secretary and note the quality of English. In addition to the programs listed above, the CSD also has ESL courses, opportunities to develop informal conversational skills, and community English language classes.

How do I motivate a student who is struggling?

- Communication with the student is important. Talk with the student and try to get to the root of the problem. Ask if the student is still interested in their research. If the answer is no, you have identified a serious problem. Ask the student if there are obstacles hindering their progress. You may be able to clear the obstacles or provide guidance on how to tackle the obstacles.

- The student needs to know if their status is at risk. Be frank and let the student know they won’t finish by continuing on the present course and recognize they may not. The supervisory committee can also help provide this feedback to the student. Two consecutive notations for "unsatisfactory progress" will require the graduate studies committee to make a decision regarding student status.

How do I deal with mental illness in students?

- Sympathy is not enough. It is important to recognize when your listening skills are not sufficient. You can ask questions about support groups and friends, but some students will need some professional help. Encourage them to seek help, for example it can be helpful to ask for their permission to facilitate a call to the Centre for Student Development while they are present in your office. Maintaining student confidentiality is important.

Can I dismiss a student who just can’t cope?

- The best solution will vary depending on the particular situation and the student. Consult with your department Chair and the Faculty of Graduate Studies.

How do I keep my graduate students focused while on sabbatical?

- Send postcards indicating specific things to do.

- Find a colleague willing to provide on-site advising.

How do I handle differences in success rates and jealousy between students?

- External grants are often a source of jealousy. Try to contextualize success and failures to obtain grants. Share your own experiences of failure with students. For example, you may know the success rate for particular grants is very low.

- If a student with low motivation is thinking of transferring to a PhD, it is usually a bad decision. It is easier to work with students than pull them along.

How can I avoid Academic Integrity problems with graduate students?

- Learn what you can about the university policy on Academic Integrity and requirements. Find out if your department has a policy itself and find out if your students are aware of these policies. For example, in Biology, students are required to take a workshop on Academic Integrity and to sign a form. Try to address this issue early and be clear. For example, students sometimes cut and paste verbatim from other sources early in drafts. Address and discuss this early on to avoid confusion later. Be aware pressure can lead some students to plagiarism. They need to realize the serious consequences of those actions. Mentoring on the topic of Academic Integrity is critical and can avoid serious problems.

- Discuss issues such as:

- Multiple submissions of work. Are students permitted to submit work to more than one course?

- Misrepresentation, e.g. Is it acceptable to put the title, “Dr.” on their name card or in correspondence?

How do I help students manage stress regarding comprehensive exams?

- Comprehensive exams can be extremely stressful for students. One visa student began panicking about comprehensive exams two weeks after starting the program. Assure students it is okay to admit they don’t know something. In a comprehensive exam professors are judging the student’s ability to think on their feet, and their ability to deal with the limits of their knowledge.

- Helpful strategies include:

- Offering to “train” them— with mock sessions.

- Demystify the process. Explain the procedure and objectives.

- Connecting the student with someone who has recently done a comprehensive.

How do you know when a student is stuck or running into problems?

- If your student stops coming to see you, misses meetings, or is silent, they are likely experiencing some type of problem; there may be other causes, but you need to find out. Keep communication lines open. With experience, students learn research has fast and very slow periods. If things are moving quickly and begin to slow down they sometimes believe all progress has completely stopped and begin to lose heart.

- To get students unstuck you can:

Send a quick email. Is there something I could be doing for you right now?

- Ask them, “Are you experiencing any obstacles right now?” Signal you are willing to help with

- “obstacles” outside their control, for example, making contacts with key people or facilitating

- access to equipment that is in demand.

- Set clear targets for the student to aim toward so they can have a sense of making progress.

Also see McMaster’s guidebook (PDF format) Good Practice in the Supervision & Mentoring of Postgraduate Students.

Related Resources

Guiding Principles for Graduate Student Supervision (PDF) is written by the Canadian Association for Graduate Studies (CAGS) 2008.